Just over a week ago I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to document the closure of a family run Port Talbot landmark, the Royal British Legion. The following images were shot in 3 sittings over 2 days and are split by 1 – Before opening 2 – The Final Call (the final bingo and snooker games) and the following night, 3 – Fond Farewells (the last night of the Royal British Legion).

It was a real privilege, and though I hope to do it justice, I know the words and images below can only capture a small part of what the Royal British Legion meant to the people who spent time there. I will always be grateful to John and Alyson, who ran the Legion for 43 years, as well as raised their family in the accommodation above, for allowing to me to go and document the final days of the Legion.

1 – Before opening

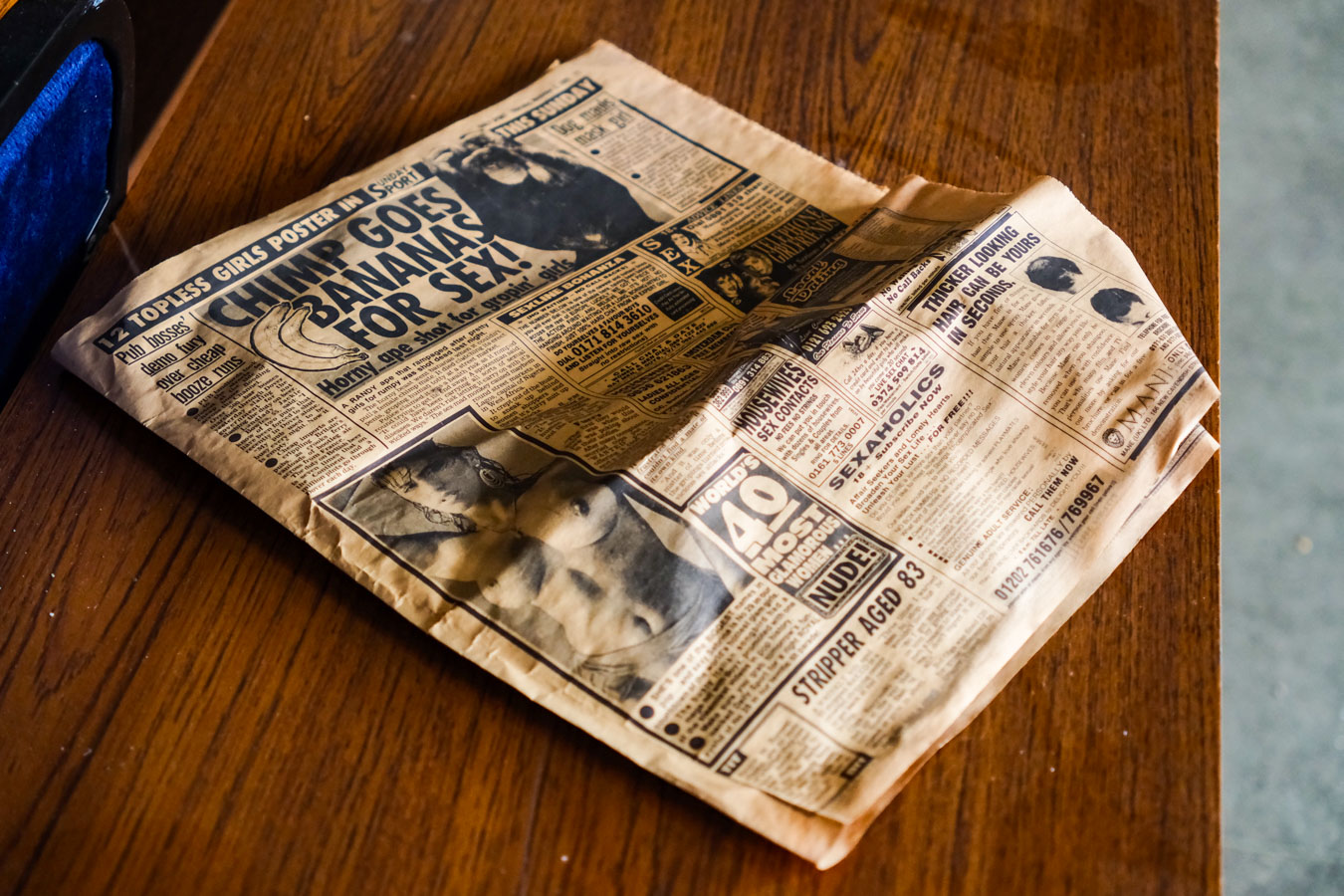

The first morning (Friday) I had the chance to go in and explore the Royal British Legion. I had free reign to take photos and wander the space on my own. What draws me to places like this is something that feels rooted in my own past—something I imagine a lot of people from the valleys would recognise.

Unlike modern spaces, sterile Starbucks clones or the charmless sprawl of a Wetherspoons. places like the Royal British Legion don’t just exist, they have existed. You feel it in the walls, the wear, the way the furniture hasn’t changed in years. There’s a weight to it.

One thing I’ve always struggled with in documentary photography is the line between documenting and mocking. I think it’s a particularly “valleys boy” problem. The idea that by noticing things, you’re somehow setting yourself apart, or trying to be better than. That to observe is to ‘other’.

But still, I try to find and record the details, especially when it’s likely they’ll never be recorded again. The Royal British Legion wasn’t the centre of the community because of its upmarket decor. But every part of that building has meant something to someone, at some point.

It wasn’t until I started speaking to regulars or showing them photos, sparking memories that I really began to understand how much of them is tied up in that place. The building and the people are woven together over time, in the smallest of details.

2 – The Final Call

I returned on the Friday night. I’d been told it was the last chance to get photographs of the pool players. Honestly though, I was far more excited to shoot the bingo.

As you’d expect, a 6-foot-3 bald bloke wandering around with a camera while people are just trying to enjoy their pint put a few on edge. I only got one “Who the fuck is that, then?” all evening, which felt like a result. That unease definitely eased off as the night went on and as the beers went down.

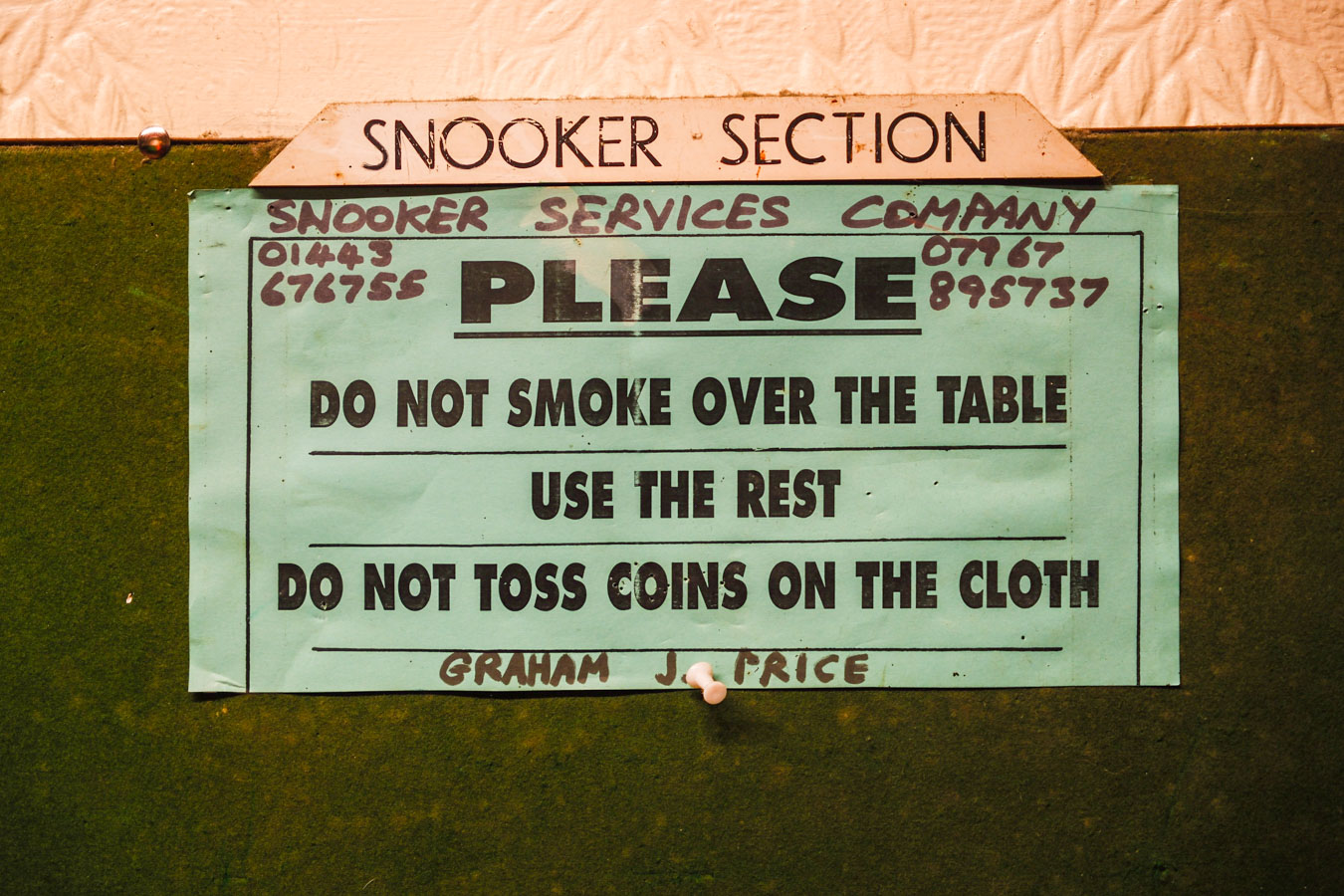

Snooker was downstairs, bingo upstairs. Downstairs was full of chat and laughter, but come the strike of 8pm, you could hear a pin drop in the upstairs lounge.

I’d arrived early for the bingo and was quickly warned about where I’d left my camera bag. THAT was someone’s seat. As much as I enjoyed the snooker lads and their banter, it was the ritual of the bingo that fascinated me.

Everyone had their seat. You approached John Pugh individually for your cards (God help you if you handed over a twenty or if he wasn’t quite ready). The calls were met with an almost drone-like rhythm “Two little ducks” a quiet, synchronised “quack quack quack” in return. The way everything was laid out – the board, the dabbers, the glasses—was precise, meticulous. A weekly ritual, played out in the same seats, week on week, for longer than many could probably say.

3 – Fond Farewells

Back for the closing night. A few recognised me from the evening before, and as anyone will tell you, in a place like the Royal British Legion, a day is a lifetime so I was welcomed with open arms.

The staff were expecting a quiet one. They were in for a rude awakening. The place was packed until closing time.

There were regulars, former staff, and even people who had never drunk in the Legion before. Plenty of laughs, plenty of stories and, thankfully, no one swore at me this time. But there was also a real sense of an ending.

I spoke to as many people as I could, listening to their memories. A father and son stood looking at an old telephone booth (no longer home to a phone) and told me how the father once got the call there to say his wife had gone into labour. He had to forfeit his league match and rush off.

Someone else told me about the joke trophy for an old boy long passed “champion gurner.” Another remembered how the darts lads used to write clues to crossword puzzles on the scoreboard when they got stuck, hoping someone else might come along and fill in the answers.

At one point, someone said to me, “Where were all these people before, hey? If they’d come earlier maybe it wouldn’t be closing.”

But that’s not really how the world works, is it? It’s a fair point, but sometimes we only return to these places out of nostalgia. And nostalgia, by its very nature, is for something that doesn’t exist anymore.